Tonight I will be attending the reopening of Tavern of the Green under new owners. I made my New York City debut at Tavern on The Green in April, 1981. It’s a very lovely story and, because it is so timely, I am going to dare to post an extremely rough, unedited and probably too long draft of the event from my upcoming-some-day memoir. It starts at the point in the manuscript where I had just finished a week of cooking with Chef Paul Prudhomme at K-Paul’s in New Orleans:

The week ended much too soon and I went back to my little catering business in El Paso, a changed woman. I had seen how exciting the restaurant business could be, experienced the instant gratification of customers telling me how much they loved my food, and instinctively knew that this was what I had been born to do. Moreover, I knew that this was the break that I had been hoping for. Chef Paul was revered and inspired respect and adulation. He was a superstar and I had worked by his side for one whole week! Surely, some of his magic would rub off on me.

A month later Paul called to share the news that he’d been invited to cook for 120 noted French members of the Confraire des Maitres Cuisiniers, at New York’s landmark Tavern on the Green. By now, mother was metamorphosing into Madame Aida, stage mother extraordinaire, and she chided me for not asking to be taken along. I’d never do that and she knew it, but, as luck would have it, fate stepped in. A few days later Paul called to ask: What are you doing on April 21st (I think.)

The party had grown to more than 500 guests and Paul didn’t feel that he could execute his food up to his standards for such a large number of people and the concept of the dinner had to be changed at the last minute. It turned out to be one of the first, if not the first, regional American food buffets. Alice Waters came from California with her boxes of home grown baby lettuce, Leo Steiner of the Carnegie Delicatessen served pastrami and corned beef, Seppi Renghli made Italo-American food, Michael Tong presented Chinese-American, Maida Heatter provided an infinite variety of cookies and desserts, but they needed someone who could do Tex-Mex food. Presto!, Paul suggested me. I refused at first. It seemed such a daunting task. I told him that I couldn’t even chop an onion like a chef and he said, “You don’t have to. You’re the chef. Just say bring me a chopped onion.

He flew to El Paso to help me plan the menu and determine the ingredients, amounts needed and how to pack them securely for transport. Though Paul didn’t know it, there was very little Tex-Mex on the menu besides the border beef salad called salpicón, pork in red chile sauce and homemade flour tortillas. Mother and I were not about to serve gloppy nachos and enchiladas and combination plates were out of the question. Instead we decided to round out the menu with crab enchiladas and red snapper hash.

Paul also wanted me to know what an important role the press can play in a career. They bring you to the attention of the world at large and he wanted to make sure I made no missteps. He said they would ask me if my cooking was authentic and stressed that I should reply that this was MY food.

In no time at all, Mother and I and our numerous perfectly packed boxes were being met at La Guardia International Airport by one of the assistant managers, Tony Zazula, who was elegantly attired in a grey cashmere coat with black velvet lapels. We were taken to the Essex House hotel in a limousine. Mother was in heaven; I was scared to death. We would be there three days, the first two leading up to the final event: the 500-person dinner.

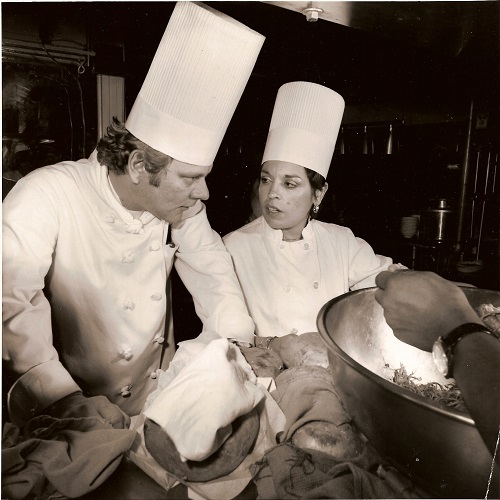

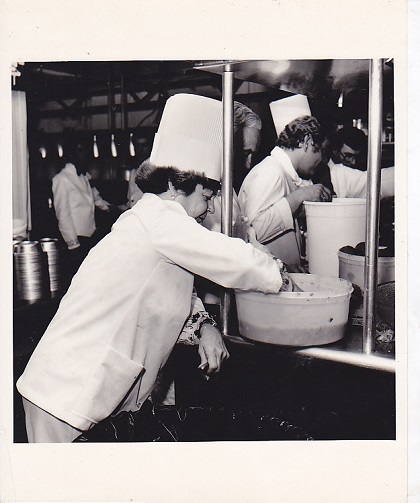

The next morning we were at the kitchen at Tavern and when mother pulled out her dime store serrated knife, screen idol gorgeous, Pierre Franey, once chef of the legendary Le Pavillon, stepped in as sous chef. The kitchen was abuzz. Pretty soon we had an audience drawn by the unfamiliar aromas. Used to common Tex-Mex fare many of the chefs wondered if this really was Mexican food. And who would think that a fish with aromatic spices like canela, cumin and cloves could explode on your palate? And crab enchiladas? Most had never tasted two of our universally beloved flavors: piquant, refreshing tomatillo sauce and the earthy smoked chipotle chile in the salpicón. The bakers gathered around to see my mother roll out little flour tortillas with the baby rolling pin she always carried in her bag. She was on center stage and loving it.

This glittery décor of this legendary restaurant reflected the Hollywood background of its owner, Warner LeRoy, son of Mervyn LeRoy, who directed The Wizard of Oz. Warner got to keep Toto after the movie production ended, and he was another large and larger than life character who would play a big role in my life. He was eternally fighting his weight and some time later I asked him if he had lost some weight and he answered: “Thousands of pounds, honey, and I put them right back on!” Warner was of the if-you-can’t-hide-it-decorate-it approach to wardrobe and loved to wear outrageous embroidered brocade, silk, velvet, or lame jackets. He had a cherubic face, a broad smile, a generous heart and I always think of him with wide-spread welcoming arms.

He invited us for lunch in the luxurious, if gaudy, Crystal Room with the chandeliers from the set of Gone with the Windi. Every day we proudly followed the maitre d’ in our uniforms reeking of fried garlic and onion to a beautiful corner table and ate smoked salmon and lobster salad (the only safe things to order in a restaurant that seats 1500) to our hearts’ delight and Mother somehow finagled two complete rose-decorated place settings that she treasured until the end of her life.

When he got back to the kitchen, Warner yelled at the porters to keep the floors dry. The in-house florist shop was bursting with a riot of flowers, spilling water into the kitchen and the floors were quite slippery. There was a complaint from the ASPCA when the organization heard that live goldfish were being used in the flower arrangements, The New York Post came around to snoop and they had to be nixed. Craig Claiborne, food editor of the New York Times, watched every step, furiously taking notes. It was all high drama.

Warner asked if there was anything we’d like to do that evening. Paul wanted to hear Pavarotti singing with Joan Sutherland that night at Lincoln Center but tickets were impossible to get. Warner called Paul to say: “I spoke to Gambino (the Mafia boss) and he said he could get the tickets but he’d have to murder four people so how badly do you want to go?” “We’ll make other plans” was the answer.

We went restaurant hopping instead and it was astonishing to see what a sensation Chef Paul caused everywhere we went, commanding attention by his utter star power. People fairly bowed down to him and he took it all in stride, elegantly and restrained, focusing intently on each person and talking to them in his quiet voice, endlessly signing autographs. I had found something to strive for.

The event was a resounding success. Now-famed restaurant empresario, Drew Nieporent, was the banquet manager. After dinner was served, I walked into the Crystal Room and sat at the first empty seat. Everyone was up and clapping. Arthur Schwartz, then food editor of the Daily News, said to me: Stand up and take a bow –that’s for you. .(I realized later that mother had purposely stayed back to let me bask in the moment.) That was pretty heady stuff for a young girl and Paul sat me down the next day and told me that I had been living in fairyland the last few days and that there would be a lot of press coverage, filling my head with dreams, but that I would be returning to the ladies luncheons and cocktails parties in El Paso and that I shouldn’t believe in what I read in the press. “ You’re only as good as your next meal.”

It was a lesson I never forgot.